Follow WOWNEWS 24x7 on:

The Election Commission of India’s Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of electoral rolls, launched ahead of key state elections, has ignited a nationwide conversation about voter inclusion, documentation access, and democratic fairness. While the exercise aims to clean up outdated voter lists and ensure electoral integrity, critics warn that its stringent document requirements may disenfranchise millions—especially the poor, marginalized, and undocumented.

Here’s a comprehensive breakdown of the issue, its implications, and the voices shaping the debate.

1. What is the Special Intensive Revision?

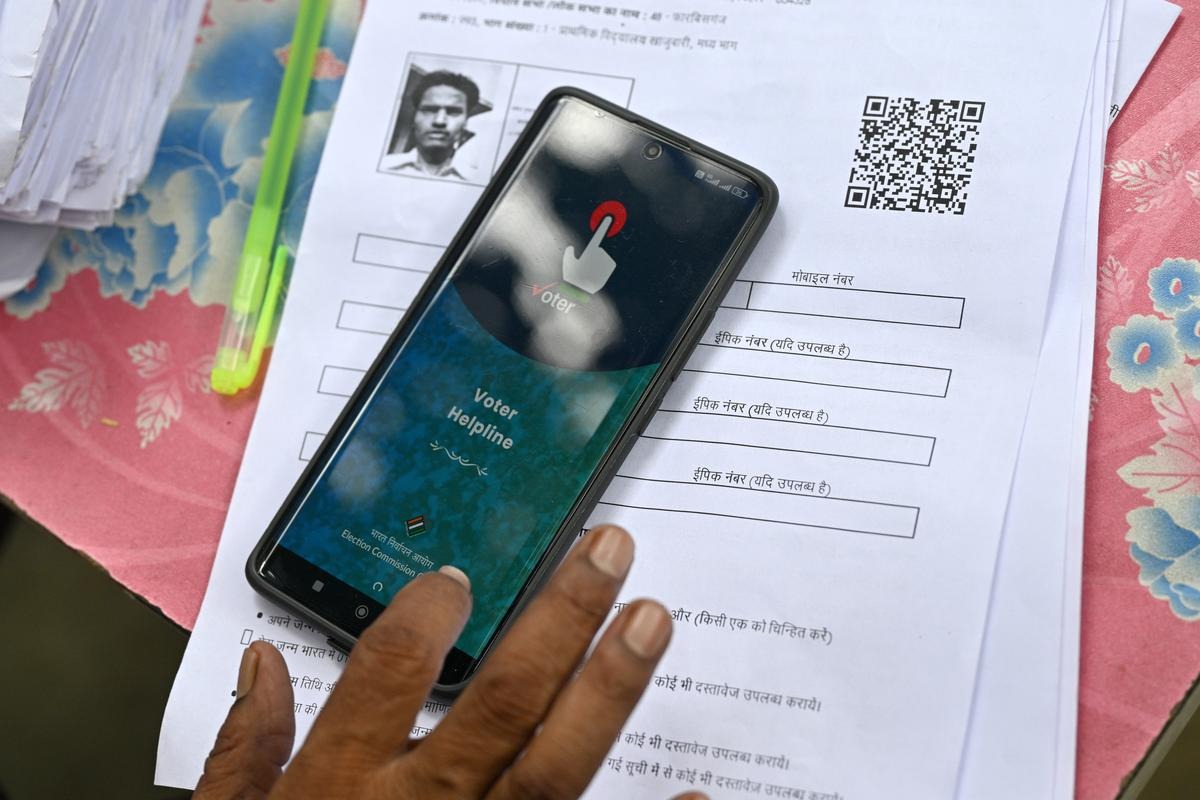

The SIR is a door-to-door verification drive initiated by the Election Commission to update voter rolls from scratch. It began in Bihar and is expected to expand to other states. Officials visit households to verify voter details, add new eligible voters, and remove duplicates or invalid entries. Unlike routine annual updates, this exercise demands documentary proof of birth and citizenship, especially for those born after 1987.

2. Key highlights from the rollout

- In Bihar, the SIR requires voters born after 1987 to provide their own birth certificate and at least one parent’s citizenship proof

- Those born after 2003 must submit both parents’ citizenship documents

- The Supreme Court allowed the exercise to proceed but advised accepting alternative IDs like Aadhaar, voter ID, and ration cards

- A writ petition challenged the legality of the document demands, citing risks of mass exclusion

- The Election Commission defended the move as necessary for electoral accuracy and transparency

3. Survey insights: who gets left out?

A study by Lokniti-CSDS across six states and Delhi revealed troubling gaps in documentation:

- Only 36 percent of respondents were aware of the SIR or its requirements

- Over 50 percent lacked a birth certificate

- Two in five did not possess a domicile or caste certificate

- Nearly 67 percent lacked their parents’ birth certificates

- Around 5 percent had none of the 11 documents mandated by the Election Commission

- Women and economically weaker citizens were disproportionately represented among the undocumented

These findings suggest that while the SIR may improve voter roll accuracy, it risks excluding large swathes of the population who lack formal documentation—especially in rural areas and among historically disadvantaged communities.

4. Inclusion vs. exclusion: the heart of the debate

The central tension lies in balancing electoral integrity with democratic inclusivity. Supporters argue that the SIR is a long-overdue cleanup of bloated and inaccurate voter lists. They cite urban migration, address duplication, and outdated entries as reasons for the overhaul.

Opponents counter that the documentation burden shifts responsibility from the state to individual citizens, many of whom lack access to records due to poor administrative infrastructure, illiteracy, or historical neglect. They warn that requiring birth certificates and parental citizenship proof could disenfranchise millions, especially in states with weak record-keeping systems.

5. What’s next?

The Election Commission is expected to expand the SIR to other states in phases. Meanwhile, civil society groups and legal experts are calling for safeguards to prevent voter exclusion. Suggestions include:

- Accepting a wider range of documents for verification

- Respecting past voter lists as valid proof

- Ensuring due process before deletion

- Conducting awareness campaigns to educate citizens about the requirements

As India prepares for upcoming elections, the inclusivity of its voter verification process will be a litmus test for the health of its democracy. The challenge lies not just in cleaning up the rolls, but in ensuring that every eligible citizen—regardless of paperwork—has a voice at the ballot box.

Sources: The Hindu, Lokniti-CSDS, IAS Express, Vajiram & Ravi, Economic Times, The India Forum, Supreme Court filings